(Image Source: Showtime)

“The NCAA is really fucked up. Everybody’s making money except the players. We’re the ones waking up early as hell to be the best teams and do everything they want us to do. And then the players get nothing. They say education, but if I’m there for a year, I can’t get much education.”

These are the words of NBA star Ben Simmons in the HBO documentary One and Done, which chronicles Simmons’ journey from being a young basketball prodigy in Australia to coming to the U.S. and attending Louisiana State University before finally realizing his dream of joining the NBA. The documentary highlights, among other things, aspects of college sports which many consider to be clear weaknesses and failures by universities and the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). These include the lack of pay for stars like Simmons, who generate millions of dollars for their respective universities; the corruption that takes place in both academic and financial contexts; and the hypocrisy of universities and the NCAA, who label these stars ‘student-athletes’ even though they often seem more like employees than students. Many argue that high-profile college athletes, particularly the ones who participate in lucrative sports like football and basketball, are being exploited because they are only being paid through scholarships, which are not worth much compared to the amount of money these athletes generate, and they have a strong case when one considers the numbers: the NCAA reportedly generated over a billion dollars from college sports in 2017 , and some college sports programs make upwards of one hundred million dollars annually, mostly from their basketball and football teams.

However, it is also important to note that most college athletes do not fit into this high-profile category. According to the NCAA, only two percent of college athletes in major sports like basketball, football, and baseball go on to become professional athletes, and only a handful of this group consistently makes headlines and attracts national media attention. For the vast majority of Division I athletes, college sports offer a pretty good deal: scholarships, which often cover one’s full tuition and fees, along with the opportunity to compete in one’s respective sport. Of course, this is assuming that the athletes receive a quality education, which, after observing scandals like the one involving fake classes at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is a big assumption to make; if the NCAA is going to continue using the term ‘student-athlete’ to refer to college athletes, then it must work with universities to ensure that such scandals do not occur in the future and that college athletes actually receive a quality education.

One can also benefit from other perks that come with being a college athlete, including access to alumni networks, the potential ability to impress employers with one’s experience as a college athlete, and sometimes even fame. Even those who do pursue professional sports can benefit from the system; one name that comes to mind is C.J. McCollum, an NBA player who earned his degree in journalism at LeHigh University and continues to be actively involved in journalism today. For people like McCollum, universities offer a mutually-beneficial agreement in which they profit off of the student-athletes who, in return, receive a free education and the opportunity to compete in their respective sports.

However, for the minute minority of college athletes like Ben Simmons, who are largely responsible for the enormous profits generated by college sports, the current system is unfair because television networks, universities, the NCAA, and seemingly everyone else involved in college sports profit off of them while they make nothing. This is especially concerning when some of these athletes feel forced to go to college because they are not allowed to play professionally immediately after high school. For example, the NBA has a policy often called the “one-and-done” rule, which requires one to be at least nineteen years old to enter. The NFL has an even stricter rule, which states the following: “To be eligible for the draft, players must have been out of high school for at least three years and must have used up their college eligibility before the start of the next college football season.” Some argue that basketball players have the choice to play overseas or join the G League, which is the NBA’s minor league intended for potential NBA players. But most successful NBA players come from college basketball, which best allows for one to gain national media attention and increase one’s draft stock, and it would be seen as a compromise for many to pursue anything other than college basketball after high school. However, at least basketball players have alternatives; football players have no alternatives: college is the only option.

For many of these athletes, the current system of college athletics is not mutually-beneficial because they are receiving much less in return for what they bring to their universities. This is even when accounting for the price of four years worth of tuition and fees, which is at most roughly a quarter of a million dollars—a mere sliver of the amount of money these athletes generate. However, often times star athletes do not stay for all four years because they want to play professionally as soon as they can. At one point in the documentary One and Done, Ben Simmons states, “I’m not going to class next semester because I don’t need to. I’m here to play, I’m not here to go to school.” And it is difficult to blame him. After all, he had no intentions of staying for more than one year because he knew he was headed for the NBA, where he now makes millions of dollars. He was only at college to fulfill the NBA’s “one-and-done” rule, generating millions for LSU while receiving none of it. Meanwhile, LSU pretended like he was a ‘student-athlete’ by labeling him as one while marketing him at the same time. Simmons sums up his experience being on the receiving end of this hypocrisy: “Everybody knows who I am because LSU [markets] me and put me everywhere. They’re gonna treat me like I’m a superstar and then the next day say that you’re not, you’re just another student-athlete. They can’t expect me to act like everybody else if they don’t treat me like everybody else.” If universities are going to continue exploiting star athletes like Simmons, they ought to admit it instead of hiding behind the guise that they are no different than the rest of the college athlete population.

This hypocritical practice is not unique to LSU, nor is it unique to this time period. In a piece titled “The Shame of College Sports,” Taylor Branch of The Atlantic discusses, among other things, how colleges have used the term ‘student-athlete’ throughout history to exploit college athletes. In particular, Branch sheds light on the case of Kent Waldrep, a former running back who played for Texas Christian University’s football team before being paralyzed everywhere below the neck after incurring an injury during a game on October 26, 1974. The university paid for his medical bills for nine months before refusing to pay any more. Branch elaborates on what followed: “Through the 1990s, from his wheelchair, Waldrep pressed a lawsuit for workers’ compensation...The appeals court finally rejected Waldrep’s claim in June of 2000, ruling that he was not an employee because he had not paid taxes on financial aid that he could have kept even if he quit football.” Universities have since continued to use the term ‘student-athlete’ to refer to an ideal that rarely becomes actualized and often serves as a facade for the reality of college athletics. Branch does not hesitate to call out this hypocrisy for what it is: “The long saga vindicated the power of the NCAA’s “student-athlete” formulation as a shield, and the organization continues to invoke it as both a legalistic defense and a noble ideal. Indeed, such is the term’s rhetorical power that it is increasingly used as a sort of reflexive mantra against charges of rabid hypocrisy.” It is time that universities and the NCAA acknowledge the gloomy realities of today’s college athletics system, including the fact that it takes advantage of some athletes, rather than continually pointing to the symbolic student-athlete experience which is foreign to many college athletes.

Clearly, something ought to be done to better compensate these athletes, and there are different ways of doing so. Some argue that the solution is for universities to pay them as a means of compensation, but this would present countless more issues to address. One immediate consequence would be that universities would have fewer resources to invest in other areas of their respective campuses. This would be in addition to the amount they already invest on sports, which can sometimes be ludicrously high. (One need look no further than the renovations done on Texas A&M’s Kyle Field, which cost roughly half a billion dollars and was considered “under budget.”) Things become even more complicated when trying to determine the amount of money that the athletes be paid. Would athletes who compete in high-revenue sports like basketball and football be paid more than those who compete in other sports? Or would all athletes be paid the same amount, regardless of sport? If basketball and football players were to be paid more, then those who compete in other sports would likely protest to this, arguing that they are being unfairly treated. The basketball and football players would contend that they should be paid more because they bring in more money for their universities. Each side presents a strong case; thus, we find ourselves in a hopeless dilemma: which side should we choose? Unfortunately, both paths lead to more questions without clear answers.

If athletes were to be paid equally, then it would be uncertain how much they ought to be paid. Would the NCAA decide on a set number for all athletes? Or would individual universities determine an amount for only their student-athletes? If the former were to occur, it would be unclear whether or not there ought to be distinctions in pay among Division I, II, and III athletes. In the latter scenario, universities with greater endowments would have an unfair advantage because they would be able to pay their athletes more and, thus, attract top recruits to play for them. It could be argued, however, that this would not solve the issue of parity since only a handful of universities, especially those in the major sports conferences like the SEC, Big Ten, Pac-12, and ACC currently dominate most collegiate sports anyway.

Paying athletes unequally would also present difficult issues. For instance, it would be unclear if there ought to be a difference in pay among individual athletes who compete in the same sports. Some would argue for this disparity because individual players often vary in their contributions to the overall revenue their teams generate. For example, a star quarterback will often attract more of the media’s attention than his teammates on defense. But others would argue that those on defense contribute just as much to their team’s success and deserve equal pay even though they do not receive as much attention. Another factor to consider is the potential effect this would have on athletes’ relationships with one another, both within and across sports. Differences in pay would likely create drama and conflict which could potentially disrupt locker rooms and even affect a team’s overall performance. Paying athletes, unequally or not, would also further alienate them from the rest of the student body because of the distinction between being paid and not being paid, which would likely spur animosity within the non-athlete student population and make the label ‘student-athlete’ even more hypocritical.

All these questions have no clear solutions, and universities and the NCAA would receive backlash from athletes, the media, and the general public no matter which way they were to proceed. And while this is to be expected for any change to occur, realistically there would be far too many challenges to face to accommodate such a small percentage of the college athlete population, and this is before even considering potential repercussions due to Title IX. A component of the Education Amendments Act of 1972, Title IX states that “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Title IX is often applied to various gender discrimination cases in college athletics, and it would almost certainly be applied to the case of paying college athletes if they were to be paid differently based on the revenue generated by their respective sports, which would favor men’s sports. However, even though paying college athletes may not be a feasible solution, this does not mean that the NCAA should not explore other options of compensating athletes who are not being adequately rewarded for their services.

A more promising solution would be to allow college athletes to sign endorsement deals. Stars like Ben Simmons would be paid, and universities would not have to pay a dime. Rather than universities or the NCAA deciding on the amount, the brands providing the endorsements would be able to decide how much to pay the athletes based on what they deem to be appropriate, just like how they sign endorsement deals with professional athletes.

There would be no issue of determining who ought to get paid because only the athletes whom brands would want to sign deals with would get the deals. Universities would still be able to give out scholarships like usual, and the system would remain largely unaffected. Some may argue that this would also lead to issues with Title IX, which may be true, but at least universities would not be the ones paying the athletes in this case. Of course, there would still be challenges with this method, but it would also avoid many of the problems that come with paying college athletes directly.

No matter which approach universities were to take, it would be difficult to enact changes in policy to reward star athletes beyond providing scholarships. But regardless, something must be done. Fortunately, there seems to be hope within the realm of basketball, as there have been recent steps toward abolishing the NBA’s “one-and-done” rule by 2022, although recent discussions have been met with obstacles , and the G League is developing a new one year program that would pay top recruits $125,000 and allow them to sign endorsement deals. However, while these are positive steps forward and other professional sports leagues should follow suit, the NCAA and universities are still responsible for their malpractices. To address the multitude of issues surrounding college athletics, the NCAA and universities must first acknowledge their roles in perpetuating these problems and strive to serve college athletes in a way that aligns with their goals. Only then will there be any hope of solving them.

Works Cited

Axson, Scooby. “NCAA Reports $1.1 Billion in Revenues.” Sports Illustrated, Sports Illustrated,

7 March 2018, https://www.si.com/college-basketball/2018/03/07/ncaa-1-billion-revenue

Ben Simmons. Sho, Showtime, https://www.sho.com/titles/3437256/one-and-done-ben-simmons

Branch, Taylor. “The Shame of College Sports.” The Atlantic. Oct. 2011. The Atlantic. Web. Accessed 28 Nov. 2018.

Gaines, Cork. “The 25 schools that make the most money in college sports.” Business Insider,

Business Insider, 13 October 2016, https://www.businessinsider.com/schools-most-reven

ue-college-sports-2016-10/#25-ucla--969-million-1

Gardiner, Jon. “UNC-Chapel Hill.” UNC, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 23 July 2018,

https://www.unc.edu/posts/2018/07/23/message-from-chancellor-folt-on-the-passing-of-president-emeritus-c-d-spangler-jr/

Givony, Jonathan. “G League to offer $125K to elite prospects as alternative to college

one-and-done route.” ESPN, ESPN, 18 October 2018, http://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/i

d/25015812/g-league-offer-professional-path-elite-prospects-not-wanting-go-one-done-ro

ute-ncaa

Jackson-Gibson, Adele. “Title IX’s 45th Anniversary: Four Title IX lawsuits that rocked the

world of women’s sports.” Excelle Sports, excelle sports, http://www.excellesports.com/n

ews/lawsuits-title-ix-womens-sports/

“Kyle Field Redevelopment Came In On Time and Under Budget.” Texas A&M, Texas A&M

Today, 13 January 2016, https://today.tamu.edu/2016/01/13/kyle-field-redevelopment-ca

me-in-on-time-and-under-budget/

McCollum, C.J. “Why Journalism Matters.” The Players Tribune, The Players’ Tribune, 11

March 2016, https://www.theplayerstribune.com/en-us/articles/cj-mccollum-portland-trail

Blazers-why-journalism-matters

McIntyre, Jason. Ben Simmons. The Big Lead, USA Today Sports, 12 Mar. 2016, https://thebiglead.com/2016/03/12/ben-simmons-is-done-at-lsu-and-it-was-an-unmitigated-disaster/

“NCAA Recruiting Facts.” NCAA, Mar. 2018 https://www.ncaa.org/sites/default/files/Recruiting

%20Fact%20Sheet%20WEB.pdf

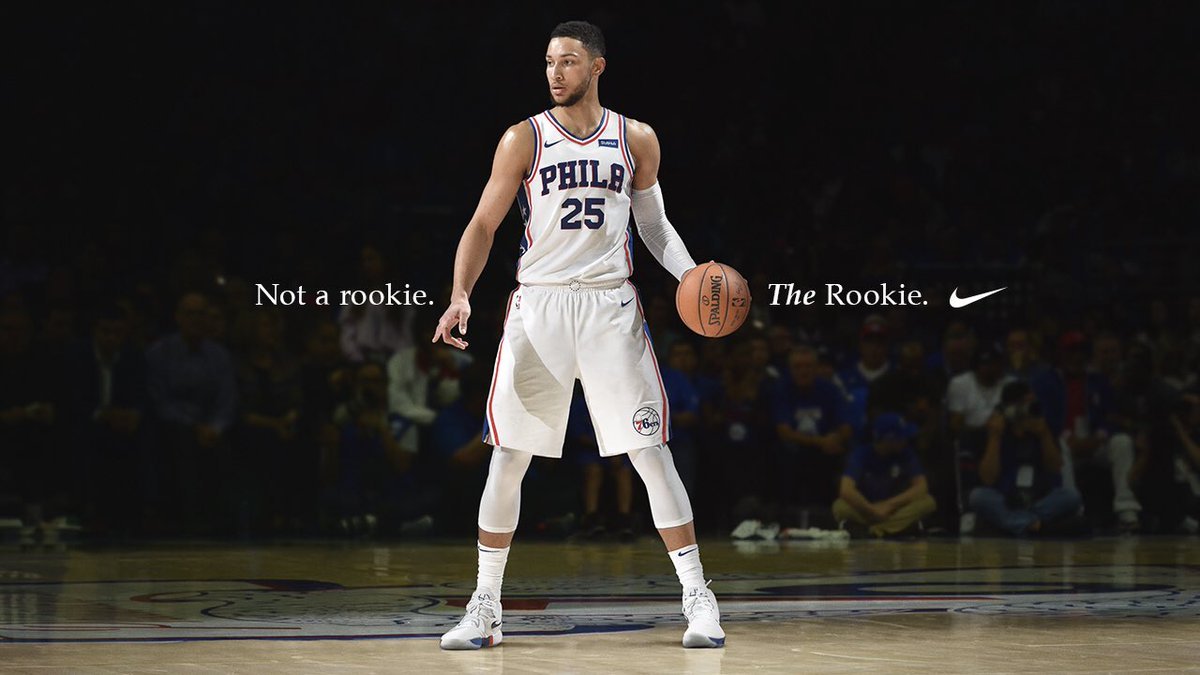

Nike. “Not a rookie. The Rookie.” Uproxx, Nike, 25 June 2018, https://uproxx.com/dimemag/ben-simmons-nike-philadelphia-76ers-rookie-year-donovan-mitchell-twitter-subtweets/

“Title IX Frequently Asked Questions.” NCAA, NCAA, http://www.ncaa.org/about/resources/inc

lusion/title-ix-frequently-asked-questions

Tracy, Marc. “N.C.A.A.: North Carolina Will Not Be Punished for Academic Scandal.” The New

York Times, The New York Times, 13 Oct. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/10/13/sports/u

nc-north-carolina-ncaa.html.

Wojnarowski, Adrian. “Sources: NBA, NBPA talks to end draft's one-and-done era hit impasse.”

ESPN, ESPN, 20 October 2018, http://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/id/25032283/nba-nbpa

-talks-ending-one-done-facing-final-hurdle.